Deaths of Tennessee children from suspected abuse or neglect rose nearly 30% in 2023

Published 9:34 am Tuesday, July 2, 2024

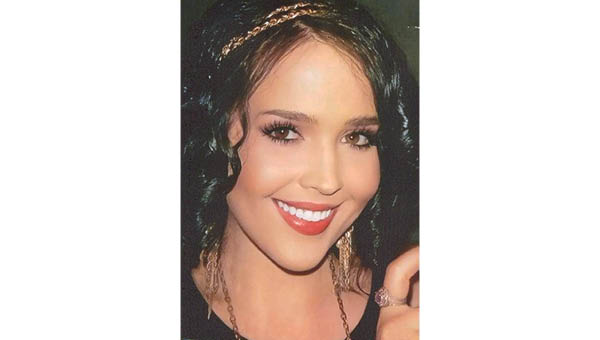

- Contributed Photo/John Partipilo Margie Quin, commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services, photographed on June 2, 2023.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Anita Wadhwani

Tennessee Lookout

A three-year-old boy shot himself in the head after getting ahold of his father’s unsecured Ruger 9 mm semi-automatic handgun.

A 4-year-old girl was discovered stuffed in a trash can, dead.

And a 3-month-old infant was found blue, still and alone on his very first day in an unlicensed daycare facility, where six infants had been abandoned by caretakers. He did not survive.

These are among the 190 children whose deaths last year are being investigated for suspected abuse and neglect by the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services — a nearly 30% increase over the prior year and the largest number of suspected child neglect and abuse deaths in Tennessee in nearly a decade, according to a Lookout analysis of DCS data.

More than two-thirds of the children had come to the attention of DCS social workers within three years of their deaths. In some instances, DCS was actively investigating a family when a child died. In others, children died after DCS had concluded its involvement with the family and closed the case.

Eleven children were in DCS custody when they died, including a 16-year-old girl who ran away from a DCS facility before overdosing on heroin in a public park.

DCS is required under federal law and a 2012 court order to publicly release case files regarding the deaths of children it investigates. Those files document all DCS interactions with the child and their family and the agency’s ultimate findings of whether the death was a result of abuse or neglect.

It may be years before the public can see those records. The agency’s review of suspected abuse deaths from 2021 is still not complete. Case files on all but 19 child deaths from 2023 have yet to be made public.

Delays keep child records from public

A spokesperson for DCS attributed the delay in investigating suspected abuse deaths to several factors:

DCS must wait until a Child Protective Investigative Team, composed of local District Attorneys, law enforcement and other members, reviews a child’s death, and considers criminal referrals, a process that can take months and sometimes years to complete, according to Ashley Zarach, a spokesperson for DCS, in response to emailed questions.

The agency also experiences lags in receiving autopsies, toxicology reports and medical records.

New laws enacted this year to fast track child autopsies for kids who had come to the attention of DCS before their deaths will help expedite the process, according to DCS.

Asked to explain the increase in suspected child abuse deaths last year, Zarach said there “doesn’t appear to be causation or a statistical significance to any increase/decrease in death cases year over year.”

“The number of deaths doesn’t follow data trends when compared against other allegations of abuse/neglect,” Zarach said, noting that child deaths during the pandemic remained steady, despite a significant decrease in child abuse reporting.

She added infant deaths related to unsafe sleep appear to be on the rise and an uptick in fentanyl and accidental shooting deaths may also be partially to blame.

Zarach did not respond to a question about whether any caseworkers faced discipline for their handling of casework involving children who ultimately died.

‘Needles in a haystack’

The deaths of children previously known to child welfare agencies have become a hot political point in recent years, pitting advocates for more removals of at-risk children from their homes against those seeking to curb the state’s power to break up families.

Naomi Schaefer Riley of the “Lives Cut Short Project” documenting child abuse deaths nationally said a current emphasis on supporting family preservation “at all costs” fails to protect the most vulnerable children and may contribute to higher mortalities from abuse and neglect.

“The pendulum may be swinging too far in that direction,” said Riley. Department of Children’s Service data reviewed by the Lookout shows that the 2023 child deaths currently being investigated outpace all other child deaths in Tennessee, which grew by 6 percent in 2023 compared to the 29% increase in suspected child abuse deaths.

Richard Wexler, executive director for the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, takes another view.

Reports of increases in the deaths of children already known to a child welfare agency often spur state agencies to become more aggressive in removing children from homes.

That would be a mistake, said Wexler, who noted that reports of child abuse deaths represent only a fraction of children agencies like DCS routinely encounter.

In the 2022-2023 fiscal year in Tennessee, for example, DCS conducted more than 66,000 investigations into child abuse and received over 100,000 reports on its hotline, according to the agency’s most recent annual report.

“These (child death) cases are needles in a haystack. So what do we do anytime there’s a spike? Report more kids, make the haystack get bigger,” said Wexler who cautioned against such “knee jerk “reactions that subject more children to the trauma of removal. DCS has tools short of removing a child to help struggling families, including substance abuse counseling referrals, parenting classes and linking families to other state services.

DCS data reviewed by the Lookout shows that the 2023 child deaths currently being investigated by DCS outpace all other child deaths in Tennessee, which grew by 6 percent in 2023 compared to the 29% increase in suspected child abuse deaths.

Black children were disproportionately represented, accounting for 39% of the suspected abuse deaths last year, while African American children under 18 make up 21% of all Tennessee’s children.

Boys are also disproportionately represented among suspected abuse or neglect deaths in 2023.

Zarach said the higher proportion of boys “appears to be an ongoing trend.”

Prematurity is more likely among male babies, who may also have higher rates of sudden death according to some studies. Boys also have a higher rate of physical abuse and accidental shootings.

Tennessee Lookout is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization. Follow Tennessee Lookout on Facebook and X.