A life with flavor: ETSU biology researcher, mentor keeps adding chapters to ‘big book of plant life’

Published 11:24 am Wednesday, August 5, 2020

1 of 4

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

JOHNSON CITY — When Dr. Cecilia McIntosh retires from East Tennessee State University one day, she hopes to leave “a whole chapter in the book” on plant biochemistry.

That goal is important to the researcher, but equally important is the legacy she leaves with her students— undergraduate and graduate— a legacy of critical thinking skills, hands-on and high-tech laboratory practices and a drive to keep asking, seeking, discovering and sharing.

Exhibiting a mathematical mind at an early age, McIntosh was encouraged and challenged by her grandfather, who gave her math problems to work in her head.

“I also always liked science, but it was difficult being a science major in college,” she recalls. “I even had one professor tell me I was wasting a spot that a man could have. Luckily, I did not listen, but there were several graduate classes where I was the only woman.”

McIntosh’s third particular aptitude was determination. She worked nearly full time the last two years of high school as a waitress and short-order cook to save for college. She was the first in her family to go to college, and with the help of her stepfather’s GI Bill, she was able to work only part time during college.

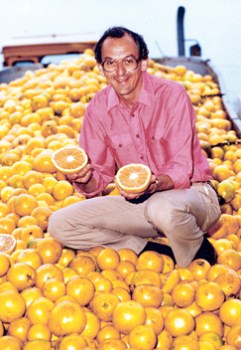

By this time, the Ohio-born McIntosh was a Florida resident and thought she would go into marine science at the University of South Florida. There she met biology professor Dr. Dick Mansell, and in him, she found a true mentor, as well as a taste for grapefruit and its research.

Mansell’s research was at that time mostly focused on processes to make grapefruit and grapefruit products less bitter. “At that time in the 1970s, the Florida welcome stations as you entered the state would have free juice samples,” McIntosh says with a laugh. “When they would put grapefruit out, nobody would take it, so we got started doing research, with funding from the Florida Citrus Commission and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Grapefruit suffers because two kinds of bitter compounds are there,” she continued. “The bitter flavonoid in grapefruit doesn’t get bitter until you add two sugars to it, which is counterintuitive. Flavor chemistry is really fascinating, so my interest as a researcher continued.”

Sugars might change a grapefruit, but the most striking change occurred in the budding biologist. McIntosh flourished under Mansell’s wise direction – not only in plant research, but also in communication and presentation skills.

“One day, he said, ‘So what do you want to do for your career?’ And I said, ‘Well, I would like your job.’ He laughed and said, ‘Well, OK, then,’ and started making me give talks. He’d say, ‘No one’s ever going to know how smart you are, if you don’t open your mouth.’ He helped me break through my intense shyness.”

While a research assistant, McIntosh not only probed ways to sweeten those tart grapefruit, but she also reared two daughters while finishing master’s and doctoral degrees. She then went on for postdoctoral research with another outstanding mentor.

“I always knew I wanted to be a scientist, but doing undergraduate research gave me a taste of the real flavor of investigation and discovery,” she says. “It’s like solving a mystery, and I love mysteries.”

Flavonoids— a group of chemicals made by plants that are involved in flower color, fruit color and some fruit flavors— have played a big role in McIntosh’s story. Flavonoids attract or repel insect pollinators, she says, and since plants are such a large part of the human diet, there has also been a lot of research into the effects of flavonoids on human physiology.

As far back as 1999, much of McIntosh’s and her students’ research and discoveries have focused on the enzyme flavonol-specific glucosyltransferase in Citrus paradisi grapefruit. She and student assistants clone and change, or “tweak,” enzymes, such as this glucosyltransferase, in differing ways and track the results.

Just before ETSU’s labs had to pause in March of this year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, she and graduate assistant Aaron Birchfield had a study published in the journal Plants – “The Effect of Recombinant Tags on Citrus paradisi Flavonol-Specific 3-O Glucosyltransferase Activity” – and another article is underway.

Like her mentor Mansell, McIntosh has propagated her passion for plant research— and education— in many young minds. Her two daughters carry on her legacy in differing ways. One is a biophysicist and the other a teacher.

McIntosh was attracted to ETSU in the early 1990s because she could both mentor and teach in Brown Hall’s laboratories and classrooms. In addition to teaching biochemistry, McIntosh trains graduate assistants in teaching pedagogy and mentoring student research. McIntosh also served as dean of ETSU’s School of Graduate Studies for 12 years, but her research continued unabated.

As technology has changed, McIntosh’s classes have as well, guided by new lab practices and computer capabilities.

“I’m going to sound elderly,” she says. “When I first started in science, all the stuff I’m doing now didn’t really exist. X-ray crystallography was known, but all the other techniques were not there. All that has come in my scientific lifetime.”

Much has changed in biological research since McIntosh began her career in the 1980s. She has changed with it. “The stuff that I teach in in synthetic biology and some of the functional genomics didn’t exist when I first started in science,” she says, savoring every molecule of research, then and now. “When I wrote my master’s thesis and my doctoral dissertation, I was still hand-drawing my figures with India ink. Now you do it on a computer.”

But McIntosh shares the best of both worlds with her students. “You just don’t stop with a computer,” she says. “You have to go back in the lab and test it and make sure that it’s real.”

There are so many new mysteries to be solved and new discoveries, especially in the field of “custom-designing enzymes” that can change the face of nutrition, pharmaceuticals, horticulture and many other aspects of life and commerce.

“It makes life interesting,” says McIntosh, who also holds the honor of being selected as one of ETSU’s Notable Women. “I’m always learning new things as we keep adapting what we do in order to learn what we want to know.”

McIntosh can reflect on 45 fascinating years of research and well over 40 journal and book publications— not to mention conference presentations and research projects that didn’t make print— and still be excited.

“I get excited every time we learn something that’s unique, that shows that there’s a different kind of a capability,” she says. “I couldn’t point to any one particular discovery. I will say that if we’re successful in getting these things crystallized and the structures known, I will feel like I have done a whole chapter in a book, the ‘Big Book of Plant Life.’

“I really feel that it will be telling the whole story. That would make me very content, then, when I retire.”