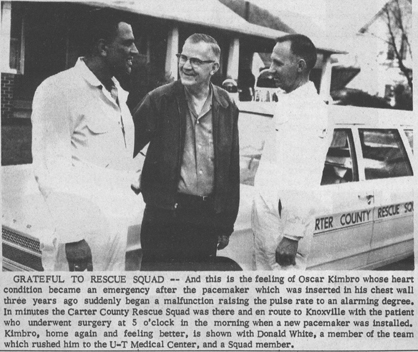

Pacemaker pays off for Oscar Kimbro

Published 12:04 pm Friday, April 24, 2020

Oscar Kimbro, who lived for many years on Academy Street in Elizabethton, for a time was one of only four Tennesseans to have a pacemaker. The device is used to control the heart rate and create a rhythmic heart.

A story in the May 1, 1966 edition of the Elizabethton STAR shared Kimbro’s story. Kimbro received his first pacemaker implant in 1963, but after three years, the device went “haywire,” resulting in a second device being implanted.

“Almost all of us live by our faith in God, but many times our life is in the hands of our fellowman in a variety of ways. It was through the help of a Knoxville team of surgeons that the life of Oscar Kimbro was again extended through the insertion of a second pacemaker at the U-T Medical Research Center,” wrote Ruby Ford, STAR Society Editor.

In effect, Kimbro’s life was operating on a battery.

But what happened when Kimbro and his life were faced with an emergency of a pulse rate which suddenly jumped from the norm of 68 to 106 and then went about as fast as it could be counted?

According to the article, Kimbro’s wife, Ethel, called seven physicians, all in Johnson City, and then made a call to the Knoxville surgeon who installed the first pacemaker with its wires and electrodes. She was told to “get him here at once.”

Through the work of Margie Gouge, secretary of the Appalachian Heart Association, the Rescue Squad had been previously contacted in the event that such a contingency arose.

Unable to secure a doctor even to take the pulse of Kimbro, the Rescue Squad went into action. From the time Kimbro entered the ambulance for the the trip to Knoxville, it was exactly 1:15 minutes until the two squad members had the patient at the U.T. Medical Center. Help for them was provided by the Tennessee Highway Patrol and police escorts took took them right through each town and along the highway keeping roads cleared for the “life and death” drive.

Then at 5 p.m., the U-T team of surgeons opened the chest of Kimbro and replaced the three-year-old pacemaker with a new one.

“It was only through the efforts of the Business and Professional Women’s Club and the Appalachian Heart Association, the new pacemaker was secured at a cost of $455,” said Margie Gouge. “And this had to be ready in advance, and it was,” said Gouge.

Now, a pacemaker — not counting the surgical procedure — will cost anywhere from $4,000 to $6,000, and this is the price of the cheapest ones.

Kimbro, who had only done some construction and building work as well as drive a taxi, had been in contact with the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, to find out what could be done to help him pay his enormous hospital bills and help maintain his home when the second attack occurred.

Kimbro shared how the Men’s Bible Class of the First Free Will Baptist Church and a friend had given him gifts of money to place on his hospital bill.

The first pacemaker was equipped with a small light which flashed each time the heart beat, but the newer model had been perfected beyond this.

The first pacemaker was used in 1952 when Dr. Paul Z. Zole of Boston Beth Israel Hospital developed an external pacemaker which sent sharp jolts of electricity to the heart. Wilson Greatbatch, an American electrical engineer, invented the first implantable cardiac pacemaker in 1958. He also invented pacemaker batteries, which were essential to its function, Nov. 3, 2014.

Both, Oscar and Ethel Kimbro are now deceased and their small cottage on Academy Street has since been razed. However, many at First Free Will still have fond memories of Mrs. Kimbrough. Oscar in his later years became a fan of the ducks on Doe River and fed them before it became the norm.

(The article about Oscar Kimbro and his second pacemaker transplant appeared in the May 1, 1966 edition of the STAR.)