If the little coal shack by the tracks could talk…

Published 8:58 am Tuesday, February 26, 2019

When Campbell Estep opened the Estep Coal Company in 1936, most homes in Elizabethton and surrounding communities heated with coal and wood. There were no electric heaters or HVAC systems.

At the time there were several retail coal businesses already operating in the community — among them Carter Coal Co. on Hattie Ave.; Harrell Brothers Fuel Co. and Pleasant Coal Company in the Rio Vista area; J.L. Hyder Coal Co. on Elk Ave.; and the B.A. Lipford Coal Co. on Holly Lane, just to name a few. There were also coal businesses on Stateline Road and in Hampton.

Coal was a popular commodity and many families bought their winter’s supply in the fall. Others bought it a ton at a time.

Trending

For many years coals were branded. Some popular brands were Blue Gem, Bonnie Blue, Red Heart, Clinchfield, Kentucky, and Red Ash. Lindberg Estep, who took over ownership of the Estep Coal Co. from his father, liked to brag about his “Red Bar” coal.

Estep Coal Co., which closed in 2013 after Lindberg’s failing health resulted in his closing the business, was the last of Elizabethton’s retail coal businesses. It had operated in the city 67 years.

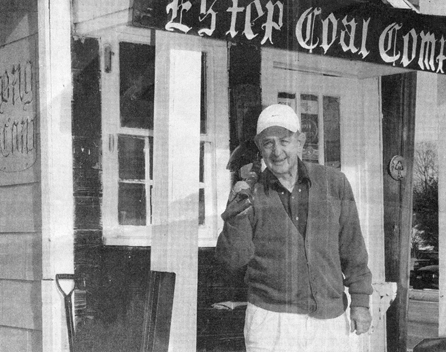

A small sign on the side of the weather-beaten coal shack notes the business was opened in 1936 and sold “quality fuel.”

The abandoned building stands right at the western tip of the downtown, offering a great view of the downtown from its front porch. For many years, Lindberg Estep ran his coal business out of the building. He would buy coal off the cars of the old East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad. He would then break his purchase down into various categories, depending on the size of the lumps of coal, and the quality of heat it produced.

That was how Estep made his money, giving poor families a chance to buy a better quality of coal for their small amount of money.

In recent days, leaders from Johnson City and Elizabethton have taken notice of the small shack and its significance to the area’s history and plans are now in the works to preserve it.

Trending

The Tweetsie Trail now runs by the little building and scattered by the trail and behind the building are small pieces of coal — a reminder of the days when Estep Coal Co. was a thriving business.

On a cold day a wisp of gray smoke curled upward from the building from the fire which burned inside an old pot-bellied stove, which Estep used to heat his office. On a wall in front of the stove was a large bulletin board, which was covered by bills of sale, receipts, telephone messages, photos, and numerous other momentos which were important to Estep. There was a story behind every one of them.

Estep was a college graduate, having attended East Tennessee State. He earned a degree in education, and later served with the United States Army during the Korean Conflict. He helped his father in the coal business when just a boy and later became owner and manager.

Estep was a one-man business. He did it all. He sold the coal, loaded it, and delivered it. His customers came from Elizabethton, Johnson City, Erwin, Roan Mountain, and even as far away as Elk Park, N.C. At the end he got most of his coal from Kentucky from small dealers, and most of it was delivered from the mine to Estep’s business by truck.

The business had long passed when the Tweetsie Trail was built. By that time, the property was shown on the deed of the Genesee and Wyoming Railroad, and there was not a hint about Estep or his father who began and operated the coal business all those years. Now that the city of Johnson City purchased the rails, the property is on a Johnson City deed, but there is no mention of the Estep Coal Co.

That is because Estep’s coal business was built on railroad property. Ken Riddle, a railroad enthusiast, in an article in the Stem Winder noted that Estep paid $50 a month rent on the property, which was due the first of each month. “Every first of the month, Mr. Hobbs from the railroad would come for the money only to be met by Estep pontificating about the low margin of the coal business and how it was an ongoing struggle to keep the contract for the school board, and all sort of excuses. Mr. Hobbs would soon tire of the whining and let loose with ‘Don’t screw me Estep, I’ll put you in the street,’” Riddle wrote.

After Hobbs died, the job of collecting the rent fell to Cecil Bowden, who Riddle said “had no use for the foolishness and excuses, so after a few months he just quit fooling with it.”

Lindberg was a creature of habit. He arrived at work and opened his little office promptly at 8 a.m. Sometimes he would visit the Southern Cafe across the street for a cup of coffee and to meet with friends. He frequently had lunch at City Market. He always looked forward to going home in the evening and having supper with his wife, Zelda.

Lindberg loved to talk and visit with his customers. He knew a little bit about most things. Riddle wrote: “He would always entertain me for a half hour or so when I visited with his philosophies on everything from politics to whether cornbread should have sugar or not, and I always enjoyed the time I spent with him. He was a natural-born comic and he and my son, Tyler, could really push each other’s buttons.”

Parked by the railroad track and the small coal shack on most days was Lindbergh’s old 1979 station wagon, painted a dull lavender. The car sort of described Lindberg — retro.

About the car, Lindberg said, “I love it. I knew when I first saw it, it was the car for me. It fits me.”

Like his car, Lindberg was fine-tuned and run well even on days when the sun shined and there were no coal sales.

Lindberg grew up in an era when a man’s word meant something and when you dressed up to go to church. He never changed.

Lindberg and his wife were the parents of two children, Lindy and Grace, and they were his pride and joy.

His other love was his church at Immanuel Baptist.

Estep Coal Company is no more, and also gone is its owners, first, Campbell Estep, and later, Lindberg Estep. Homeowners no longer use coal to heat their homes. But, the little shack by the track is a reminder of the days that were and the man who worked there to help keep people warm during the coldest winters.

In the future, when people walking the Tweetsie Trail pass the little coal shack, hopefully, they will remember the man who worked inside and his love for people and this community.