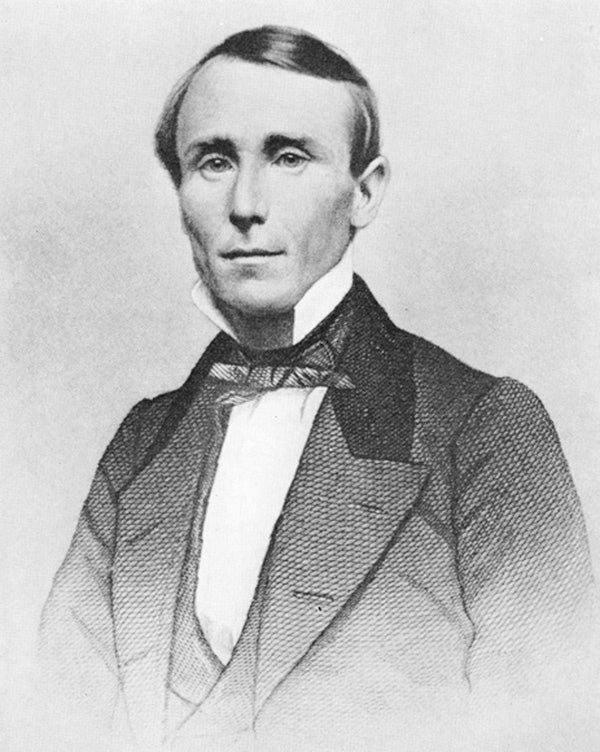

Tennessee-born William Walker invaded Central America

Published 4:11 pm Tuesday, April 19, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Among Central Americans, he may be the most famous Tennessee native. But I strongly suspect you’ve never heard of him. Born in Nashville in 1824, William Walker graduated from the University of Nashville, worked as a newspaper editor, and moved to San Francisco as part of the westward migration of the 1840s. Headstrong and pro-southern, he became convinced that the United States should expand into Central America and create slave states there. In 1853, Walker raised an army of 45 people — “reckless saloon loafers and the dregs of the California docks” — one of his biographies says, and took them on a ship to invade the area then known as Lower California and Sonora, Mexico. His group had a couple of minor military victories and took over the town of La Paz. The Mexican army forced him to retreat, and upon his return to California he was tried (but acquitted) for conducting an illegal war. About this time, Americans were interested in Nicaragua because of its role in migration from east to west. Before the transcontinental railroad, the quickest and least expensive way from the east coast of the U.S. to San Francisco was to take a ship from New York to Nicaragua, a boat up the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua, a stagecoach across a 12-mile strip of land in western Nicaragua, and a ship to San Francisco. The Nicaraguan parts of this route were controlled by Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was probably the most powerful man in the U.S. at that time.

In 1854, civil war broke out in Nicaragua. One of the political parties in that war asked William Walker for support, and in May of 1855 he sailed from San Francisco with 57 armed men. They landed a few weeks later on the west coast of Nicaragua and within a few months his army had effectively taken over the nation.

Early on, there were indications that the Nicaraguan people might embrace Walker. Among the Native American peoples of Nicaragua, there had been a legend that a “gray eyed stranger” would come to their shores and become their leader. Walker began calling himself the “gray eyed man of destiny.” He declared English the official language of Nicaragua, made slavery legal and began to work toward a long-term goal of it becoming part of the U.S. But in 1855 and 1856 several things happened that brought an end to Walker’s short reign:

* In the summer of 1855, he made peace with the leader of the opposition party, General Ponciano Corral, but a few months later accused him of treason and had him publicly executed, which turned many Nicaraguans against Walker.

* Walker’s success concerned other Central American nations, who feared that his army would eventually invade neighboring countries in an attempt to turn that region into a series of American colonies.

* Rather than ally himself with Vanderbilt, Walker took his transit business away from him. Vanderbilt effectively created a blockade of Nicaragua, sent money and arms to help defeat Walker, used his newspapers to crusade against Walker, and took steps to make certain that the American government did nothing to help him.

Vanderbilt teamed up with the president of Costa Rica and sent an army to fight Walker’s forces. And although the battles involving Walker and his army seem like skirmishes compared to the American Civil War that took place soon thereafter, people in Central America remember them well.

For instance, at the Battle of Hacienda San Jacinto, a Nicaraguan named Andres Castro turned the tide of battle when he threw a rock at an American soldier (an event celebrated in Nicaragua today). And at the Second Battle of Rivas, a Costa Rican soldier named Juan Santamaria played a key role in this battle and is today considered to be one of the great military heroes of that country (in fact, the airport in San Jose, Costa Rica, is named for him!)

Surrounded by 4,000 soldiers from Guatemala and El Salvador, Walker ordered his men to burn the city of Granada as they retreated from it. He and his remaining soldiers managed to make it back to the United States, where they were greeted as heroes.

In the summer of 1860, Walker tried to invade Honduras with an army of about 100 men. After an initial military victory, they surrendered to a British warship which turned him over to Honduran authorities. On September 12, 1860, Walker was executed by a Honduran firing squad.

As famous as Walker was in his lifetime, he was largely forgotten after his death, at least in the U.S. The people of Central America have, however, not forgotten Walker — how his army invaded Nicaragua, tried to install slavery there, and how he burned the city of Granada. In fact, Central Americans celebrate many of Walker’s defeats as national holidays.