ETSU researchers develop method of studying salamander habitat

Published 9:07 am Wednesday, July 24, 2019

JOHNSON CITY — Researchers at East Tennessee State University have developed a unique device to gauge the environmental preferences of plethodontid salamanders, and their findings could lead to enhanced conservation efforts for these critters that make their home in the Southern Appalachian region.

Salamanders are prevalent in most of the forests of the region, explained Trevor Chapman, a doctoral student in Biomedical Sciences at ETSU.

“They’re probably one of the most abundant vertebrate species out there, and they are a critical link in our ecosystems here,” he said. “They are eaten by pretty much anything that will prey on small organisms, such as owls, birds, raccoons, possums, and maybe bears, but they also prey on pretty much any invertebrate or vertebrate they can fit in their own mouths.”

Trending

However, the salamander population is currently threatened by changes in climate, shrinking habitats and fungal infections, and scientists hope learning more about the animals’ behavior will help in determining the best ways to aid their conservation.

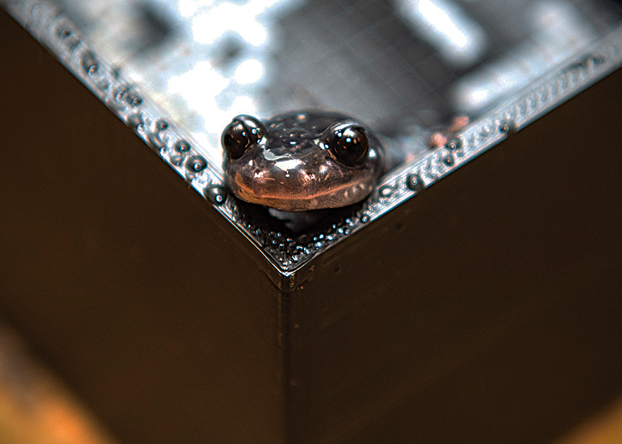

Under the guidance of Dr. Joseph Bidwell, chair of the ETSU Department of Biological Sciences, and with technical advice from Dr. Dan Connors in the Department of Engineering, Engineering Technology and Surveying, Chapman created a four-chambered device to monitor the behavior of salamanders housed within.

Chapman, who earned his M.S. degree in biology at ETSU, devised a way to induce varying temperatures, moisture levels and other factors in each of the four chambers. The floor of each chamber is not only fortified with soil and leaf material from the salamander’s natural environment, but is equipped with a load cell — similar to that of a bathroom scale — that is connected to a Keithley multimeter and a computer to detect and record the animal’s movement between the four chambers.

“Plethodontid salamanders don’t have lungs,” Bidwell said, “so they have to breathe across their skin. That’s one of the reasons we got interested in them — they have really specific requirements for environments they can survive in. They have to stay moist in order to aspire.”

So Chapman controls the environment inside the device, setting all four chambers at different temperatures, for instance, with one at 95 percent relative humidity. The researchers then place one of the Northern slimy salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus) or Gray-cheeked salamanders (Plethodon montanus) used for the study inside the device and monitor it for 24 hours to see which chamber it spends the most time in.

“Then we can go a little further and introduce other stressors, adding the chemical cues from different species that they can pick up on,” Chapman said. “Does competition with the same species or other species change where they hang out in these chambers? Are they willing to risk running into a predator of they pick up on that scent in a chamber they would actually prefer to be in? Or will they avoid it?”

Trending

Chapman added that they will also be able to test the salamanders’ stress hormones as part of the project, using a recently developed technique of swabbing the animals’ backs with sterile cotton swabs to obtain the needed fluid for testing. This will allow them to see how the salamanders’ stress levels change according to the conditions to which they are exposed.

“We’ll take that, combined with some of the climate modeling components we’ll do later on with the Department of Geosciences, to try to predict how habitat and environmental changes might affect these salamanders in the future,” Chapman said.

Bidwell said it is a great advantage to have the capability afforded by the new testing device. “It allows consistent recording of their behavior without having to disturb them,” he said. “It looks like some kind of Frankenstein experiment, but it works, and it’s just such a novel system. All the technology for this came out of our talks with Dan Connors, and Trevor just ran with it. Our work with Dan has revolutionized some of the stuff we do.

“There’s nothing like this system in the literature. Most folks are only looking at one variable, and it’s usually a visual observation system, so you’ve got to videotape it and go back and look at it. This device records everything, and you can just go back and look at the data and tell which of the chambers the animals have been in.”

As part of this project, which is supported by a $10,000 small grant from ETSU’s Research Development Committee, Chapman has been developing a mobile field lab at the ETSU Eastman Valleybrook Campus.

This mobile lab is being used to conduct field surveys at Lamar Alexander Rocky Fork State Park to see if the findings in the lab on the ETSU campus in Johnson City match their findings in the natural environment. They are using a relief model of the park, which Chapman produced using two 3D printers, to map out their testing locations.

“One of the best things is that we’re able to bring salamanders in and test them, and then release them,” Bidwell said. “One of the big concerns with working with salamanders, particularly species which might be listed by the state as threatened or a species with limited population numbers, is that bringing them back to the lab environment can stress them, and it could lead to the spread of disease. If we’re able to do this on-site, it’s safer and less stressful for the animals.

“We’ve been working with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency to get permits to do this project,” he continued, “and they’re so impressed by it that they’re looking at ETSU as setting the standard by which permits will be issued for studying these particular animals. That’s because there’s so much concern, and people want to look at these animals, but they also want to make sure they’re protected when researchers are handling them.”

The new device is already drawing interest from other scientists. Some of Bidwell’s colleagues in the ETSU Department of Biological Sciences who work with critters as diverse as spiders and bats are curious as to how they might make use of it in their studies, as is Chapman’s advisor from his undergraduate studies in environmental biology at Hanover College in Indiana.

To further support their work on this project, the researchers have applied for additional grant funding from National Geographic, and aim to apply for National Science Foundation funding soon, as well as publish their first paper on their findings.