Carter County 911 Dispatchers: An inside look

Published 8:06 am Thursday, April 11, 2019

“Carter County 911, where is the location of your emergency?” are the words no one wants to hear, yet close to 75 county and city residents do so daily.

The perception of many when they call 911 is, they will reach someone that can help them and that they will magically know what is wrong and exactly where they are.

While advances in technology have made the 911 dispatchers’ job easier, nothing happens in a vacuum. Police, firefighters, emergency medical services (EMTs) in most cases do not magically appear.

Trending

An emergency victim when everything goes smoothly is provided within minutes, professional personnel necessary to try to save their lives or provide necessary aid.

This is the result of a highly trained and dedicated 911 dispatcher on the other end utilizing a skill set that takes 40 hours to train and an additional 48 hours annually to maintain.

Carter County 911 dispatchers have the dedication to continue in the profession in the face of long hours with few breaks, low pay and lack of recognition.

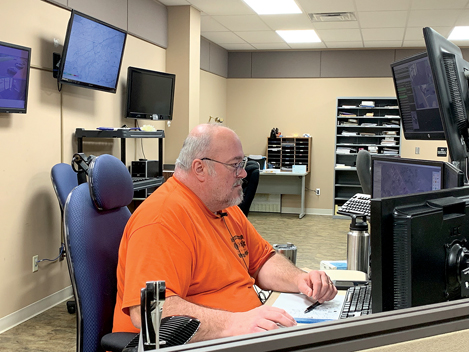

One such dispatcher, Lesia Fields, although her shift officially begins at 6 a.m., makes her way to the office an hour early every morning, like she has done for close to 18 years now.

Fields, who also serves as a supervisor, training officer, and her office’s liaison with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, says this is necessary because the process of changing a 12-hour shift is not a quick one.

The control room Fields shares with four other dispatchers is almost like walking on a set of a sci-fi movie. There are many different stations with multiple different computer screens. But every screen and button serve a purpose, and Fields and her fellow dispatchers work them with an ease that seems almost uncanny. Each station is dedicated to a certain service or agency and every dispatcher is cross-trained to work them all.

Trending

When asked why she wanted to work as a 911 dispatcher, Fields said, “I, at first, did not want to, but my husband talked me into it.” Indeed, her career opportunities were vast. After growing up in a law enforcement family with a father as a deputy sheriff, she went on to serve in the Army as a combat medical specialist. Before coming to her current position, Fields worked as an EMT-IV. Fields now plans to end her career as a 911 dispatcher.

“I have found my niche,” she said.

That seemed to be the case around the room. Many of the dispatchers have had some sort of medical or law enforcement background.

Fields and the other dispatchers said there is no typical day in the 911 control room. Some days are slower than others, but Wednesday seems to be the peak time for calls right now, they said. There is also an increase when the weather is bad.

“While I do not take calls home with me,” said Fields, “the worse ones for me involve children.” Fields also cited a time when she was able to find a female caller who claimed she did not want to live anymore. “She said she was going to walk into Watauga Lake. I talked with her about why, and she said she had two small children. I was able to use the technology we have to find her and get her some help,” Fields said.

While all of the calls received by the 911 service are always treated seriously, some are not emergencies and others involve matters that dispatchers do not handle, such as power outages.

Staff also shared some calls that were even comical, such as: a call received from a person who said there was a mysterious bright light in the sky that turned out to be the Northern star; another when some dogs got ahold of a chicken and the lady ended up putting it in a bucket to take care of it, and there are still calls where people think that the fire department will come to get a cat out of a tree.