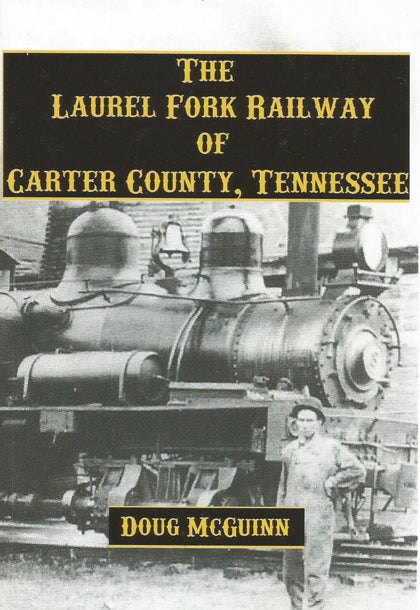

Author pens history of Carter County’s lesser-known Laurel Fork Railway

Published 10:17 am Wednesday, April 6, 2016

Contributed Photo

McGuinn’s book is, to his knowledge, the first written about the Laurel Fork Railway which ran from Elizabethton to Laban, Tennessee in the early part of the 19th century. The train pictured, Shay Number 3, was the only one he could find photos of, though two others ran on the line.

A gone-but-not-forgotten Carter County railroad will now have a permanent place in local lore, as Boone, N.C., author Doug McGuinn recently published its first complete history: The Laurel Fork Railway of Carter County, Tennessee.

“When you think of trains in that area, the first thing that comes to mind for most people is the Tweetsie, but I found out there was more than one train besides the Tweetsie, and I wanted to write about these little-known railroads,” said McGuinn.

Author of six other books on the history of railroads and industry in the Appalachian region of Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina, McGuinn’s studies focus on lesser-known subjects which played pivotal roles in the development of the region. His research from the Tennessee State Library and Archives, the Archives of Appalachia at East Tennessee State University and from old news clippings along with a handful of photographs helped him to stitch together the patchwork of this unique piece of Carter County history.

Biking along Old Railroad Grade Road in Ashe County, North Carolina in the late 90s first sparked his interest.

Contributed Photo

Author Doug McGuinn writes from his home on the history and industries of rural Appalachia.

“I figured, there’s not a railroad there, but there must have been one somewhere,” said McGuinn. “I was kind of curious, so I began research.”

What he found was a band of entrepreneurs that would not take “no” for an answer when the ET&WNC “Tweetsie” Railroad denied their request to extend railroad to their sawmill.

“To hell with the ET&WNC, we’ll start our own damn railroad!”

Lewis Gasteinger, general manager of the newly-formed Pittsburgh Lumber Company in Carter County, spoke those words in anger to William Flinn, president of the construction firm Booth & Flinn, which had in 1909 purchased 12,000 acres of virgin-timber land in the Dennis Cove region.

Gasteinger needed to transport his timber to market, and with the existing railroad unwilling to lay the rails, he opted to build his own.

“What they wanted to do was to connect the Tweetsie somewhere in Hampton and then have Tweetsie take the finished lumber to Elizabethton, where it would connect with Southern Railroad, then take the lumber North,” said McGuinn.

But that vision never came to fruition, as a deal could not be negotiated with the Tweetsie.

Thus, the gone-but-not-forgotten Laurel Fork Railway was created and incorporated in April 1910. It ran 14.9 miles from Elizabethton to Laban, Tennessee until 1925, closely following the Laurel Fork of the Doe River. McGuinn said it ran almost parallel to the Tweetsie until it passed through Valley Forge, where it turned towards Hampton.

The sawmill was located about a half mile from Hampton in what was called Braemar. The Braemar Castle in Hampton, which is now a hiker hostel, used to serve as the office, commissary and company store for the Pittsburg Lumber Company, said McGuinn.

Contributed Photo

The Braemar Castle in 1915 served as the office, commisary and company store for the Pittsburg Lumber Company, and is still in Hampton in operation as a hiker hostel.

After a cloudburst in 1924 destroyed parts of the track, he said the Southern and Tweetsie were repaired, but the Laurel Fork was not.

In addition, McGuinn said the land had been sufficiently logged.

In an effort to capitalize on remaining timber that was used for train trestles, McGuinn said the company decided to recycle and sell them.

“But somebody accidentally left a bolt in one of the trestles and it went through the sawmill, and as soon as it hit the saw, it destroyed the saw and they never replaced it,” he said. “The sawmill was then dismantled and moved to a town in Virginia that had burnt down.”

The three trains that ran on the Laurel Fork Railway were sold to separate lumber companies. McGuinn said he could only recover a photo of the third, which was sold to a company in Texas.

“All three were later scrapped during the war,” he said.

McGuinn said Laban, near Braemar, was an area which is now part of the Cherokee National Forest. The forest now encompasses most of the land the company logged, and he said a portion of the old railway is now part of the Appalachian Trail.

“If you look real, real close, and you know what you’re looking for, you can see remnants of some of the road bed there,” he said.

The story of this railway-turned-turned-hiking-trail and a lumber-outfit-gone-hiker-hostel is available online by searching Laurel Fork Railway on lulu.com.

McGuinn thanked his son, David for contributing research and photography in this year-long study. He hopes to make copies available locally soon.

Though it has just printed, he said the grandson of a man that worked at the lumber company has already thanked him for compiling this story.

His other books include Lopsided Three, The “Virginia Creeper,” Green Gold, The Railroad to Nowhere, The Last Train from Elkland, The Butterfly for Boomers, and There’s Copper in Them Thar Hills!

To contact the author, email dougmcguinn@gmail.com.